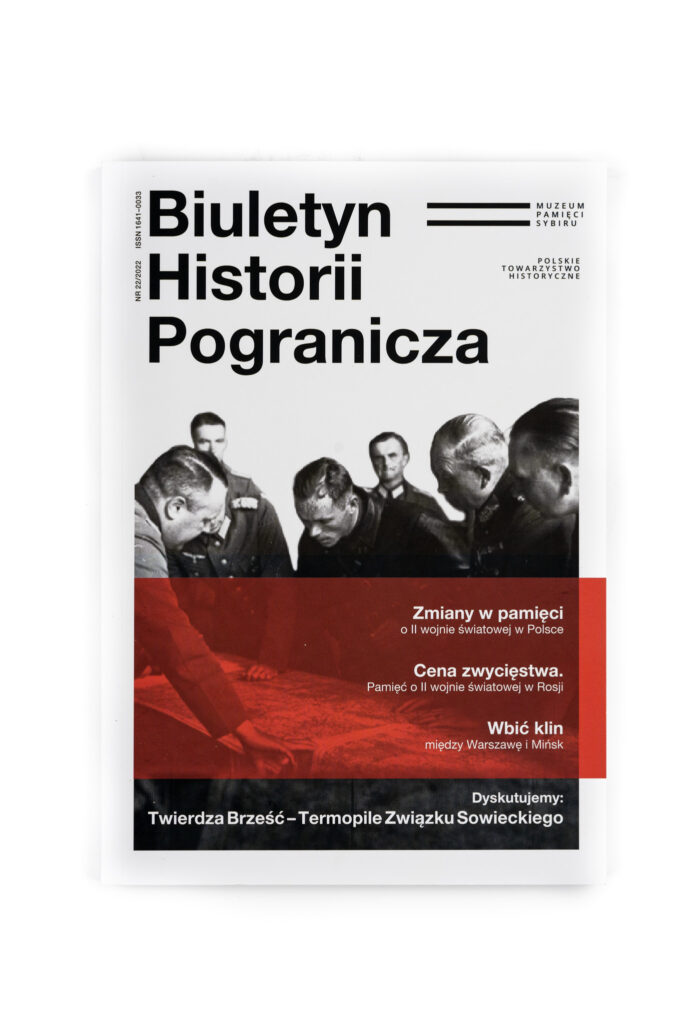

On October 6 took place the promotion of the latest, 22nd issue of Biuletyn Historii Pogranicza (Borderlands History Bulletin). The promotion was accompanied by the discussion entitled “One War — Different Memory”.

Professor Jan Szumski and professor Daniel Boćkowski took part in the meeting hosted by professor Wojciech Śleszyński, director of the Sybir Memorial Museum.

— Not without reason the conversation is held at the Sybir Memorial Museum — professor Śleszyński started the debate. — We are in the most modern historical museum in Poland, a narrative museum. Our name consists of three significant concepts of which we focus on memory.

— A human has no influence on the past, but he has influence on its interpretation. That’s the way presence contributes to the perception of the past. Memory is essential to function. An individual entity deprived of a past has problems with self-identification. In turn, having collective memory is the foundation of building a community — added professor Śleszyński.

— At which points the historical politics and memory of World War II in countries of Central and Eastern Europe is aligned and what makes it different? — asked the director of the Sybir Memorial Museum his interlocutors.

Professor Daniel Boćkowski answered: — I would also add to the discussion the historical oblivion. In the case of memory we create an image, but it also assumes erasing what doesn’t line up or what has been erased as result of political, historical processes, propaganda efforts. — Community of memory is World War II, but oblivion — it starts with the beginning of the war, what are its results, how the citizens of individual regions of Poland build the memory. How it has been cemented on a social level? Memory depends on whose message is more effective — said professor Daniel Boćkowski. — Everyone agrees that there was World War II, but in a conversation with the Russians, we would be different when it broke out: in 1939 or 1941. In turn, for political scientists it was even before 1939.

Professor Jan Szumski answered: — During the domination of the countries of our part of Europe USSR imposed its narration through commemoration and politics, school education. After its collapse, the revolutionary changes happened — countries freed from the domination were free to rise issues and we can observe a noticeable increase in interest of topics such as soviet occupation.

— In the opinion of the average Polish or Lithuanian citizen, the period of the Second World War is associated with two occupations — continued Szumski. — And right behind the border, in Belarus, Russia, the war has been around since 1941. Any discussion of Hitler’s conspiracy with Stalin is reduced to russophobia and ‘kind of revision’. We are dealing with two diametrically different visions.

Professor Śleszyński asked about common and permanent elements of memory of the war in Central and Eastern Europe. Do they concern us all?

Daniel Boćkowski said: — The narrative is built around what divides and this is the most permanent. The universal element will be the nightmare of war — the end of the hitherto history of history and development. It is a universal experience of taking over land, sovietization, building and operating the apparatus of repression and rebuilding societies in accordance with the communist vision. However, if we look at the vision of history imposed in Belarus, what was obvious in the 1990s, is no longer obvious today. In Ukraine, on the other hand, we are currently seeing an acceleration in the change of this vision.

— There are also common local experiences — said Boćkowski. — The universe is also what the Red Army that came to this area was after 1944. It was different from the 1940-41 army. This one was from a different consumption, from the lands deep within the Union, with different behaviors.

Professor Jan Szumski answered professor Śleszyński’s question: — I would like to add one interesting aspect. In the current Russian narrative (in response to a resolution of the European Parliament indicating the Soviet Union as co-responsible for war crimes), an interesting passage about the deportation of 1940-41 is interesting. According to the Russians, the deported Jewish refugees (bieżeńcy) were saved from Polish nationalists.

— The immensity of the losses and suffering in a strictly human dimension would be the common denominator — summed up Szumski. — The total war did not start in 1941, the first bombs and losses in Poland were in September 1939. The common experience would be losses and suffering suffered by civilians regardless of nationality — he said.

All those, who are interested in the subject of the memory of World War II, we recommend the latest 22nd issue of “Biuletyn Historii Pogranicza” (‘Borderlands History Bulletin’). The scientific journal published by the Sybir Memorial Museum is available in our stationary and online shop: